Adelaide Gregory Graves About 1882-1912 Texas Born Buried in Loosley Cemetery, exact location unknown (image - created using Bing AI) Adelaide was an African American woman born about 1882 in Texas to Austin Gregory and his second wife, Fannie Hanson.

Austin had been born around 1838 in Virginia, probably as a slave, which might explain how he came to be in Texas when he and his first wife, Sarah Richardson, began having children around 1855. After Emancipation, Austin married Fannie Hanson and began a second family. Adelaide married Walter Graves sometime between 1900 and 1911. However, they are not known to have had any children. In 1911, Adelaide was living in New Mexico. She had contracted tuberculosis and may have come to Phoenix in hopes of recovering. She was residing at 1509-1511 East Jefferson Street in Phoenix when she died on June 28, 1912. Her funeral was conducted from the Colored Methodist Episcopal (CME) Church located at 1401 East Adams, just a few blocks from her home, and she was buried in City Loosley Cemetery. According to her newspaper obituary, she was survived by her husband, mother, and five sisters. ©2024 by Donna L. Carr. Last revised 5 January 2024. If you would like assistance researching our interred, you can find more information on our website. You can contact us at [email protected] at any time. Thank you for your interest to preserve the history of Arizona's pioneers!

0 Comments

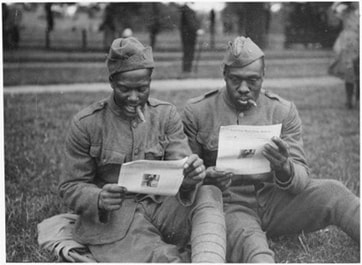

Solomon Dotson 1894-1940 World War I Veteran Buried in Cementerio Lindo, exact location unknown [image - two unidentified World War I soldiers, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)] Although no contemporary record of his birth has been found, Solomon Dotson is believed to have been born on Christmas Day, 1894, in Jacksonville, Cherokee County, Texas.

As early as August 1916, Dotson was serving as a private in Company H, 365th Infantry, U.S. Army. The 365th was a racially-segregated, all Negro regiment. However, it was somewhat unusual in that, unlike most other segregated units, it had African American officers. Dotson’s commanding officer was Captain William Washington Green. Green was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and the Silver Star for his heroic actions during World War I. Therefore, it seems likely that Solomon Dotson too saw combat during the War. Promoted to the rank of private first class, Dotson continues to appear on the 365th ‘s roster until January 31, 1919, when he was presumably discharged. The federal census of 1920 found him in Okfuskee, Oklahoma, living in the household of George Gray and working as a farmhand. In March of that year, Dotson married Gray’s daughter, Angeline. They soon had a son, Julius, and daughters Lonnie and Alice. Sometime before 1930, the Grays moved to Phoenix, Arizona, where they resided at 14th Avenue and Buckeye. A news article from that year reports that Solomon was injured in a car accident, the vehicle being driven by his mother-in-law, Mrs. Maggie Gray. By 1933, Solomon Dotson was working as a barber at the Palm Barber Shop. Proud of his World War I service, Dotson was active in veterans’ organizations throughout his later years. In 1936, he was the finance officer for the William F. Blake American Legion Post #40 (the post appears to have been renamed the Tilden White Post at a later date). Dotson’s teenaged daughter, Lonnie, was president of the post’s junior auxiliary. Dotson also belonged to the Virgil Bell Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 1710, which still exists. Son Julius Dotson graduated from the Phoenix colored high school in the spring of 1939. By the following year, he was enrolled at Phoenix College, taking art classes. 1940 was an election year, and Solomon Dotson was active in the "Wilkie for President" club. However, he didn’t live to see the outcome of the election as he died on October 15th of a cerebral hemorrhage associated with hypertension. His funeral took place at the Calvary Baptist Church, after which he was laid to rest in the Maricopa County Cemetery (now Cementerio Lindo). © 2023 by Donna L. Carr. Last revised 28 January 2023. If you would like assistance researching our interred, you can find more information on our website. You can contact us at [email protected] at any time. Thank you for your interest to preserve the history of Arizona's pioneers!  Mary A. Lee 1862-1900 African American Restauranteur Buried in Rosedale Cemetery, exact location unknown (generic image of a couple dining generated using Bing AI) Advertisement from the Border Vignette, Feb. 18, 1899 A rather breathless ad in the December 5, 1897, issue of the Arizona Daily Star, a Tucson newspaper, described Mary as "...the famous caterer who is known to prepare the finest dinner, breakfast, or luncheon in Arizona…"

The aforementioned Mary A. Lee was a single, African American woman born about 1862. Nothing is known about her early life, or where she was born, but she apparently began her culinary career at the Luray Hotel in Denver, Colorado. She appears to have entered the Phoenix scene around 1892, when she partnered with Samuel W. Slade, also from Denver, to form a catering service called Lee & Slade. By April 17, 1892, the partners were managing the dining room at the Commercial Hotel in Phoenix. In 1895, Lee & Slade were running the Opera House café, with a menu featuring "game, fish, and oysters". However, they had their sights set on something even bigger. When the newly-built Ford Hotel opened for business on November 1, 1895, Lee & Slade had secured a five-year lease for $18,000 to maintain a restaurant on the premises. However, it seems that the new hotel experienced some sort of shake-up in management as, about a month later, hotel manager L. B. Hayes resigned and was replaced by H. R. Borden. It is not known whether this change had any bearing on Mary’s relationship with Samuel W. Slade, but the partnership dissolved in 1896, and Mary sold her inventory back to the hotel for the sum of $3000. Not long thereafter, she moved to Tucson where she opened the Orndorff Cafe. To assist her, she invited A. R. Wagner, another acquaintance from her Denver days, to act as head steward. By 1899, Mary was running the Alhambra Café, advertising “Banquets and Afternoon Teas our Specialties”. She was also listed as the ‘manageress’ of the Williams Boarding House next door. Her success was remarkable for the time, as women were not often seen in managerial roles. Mary’s career was cut short, however, when she contracted tuberculosis. She gave up her lease on the Alhambra Café early in June, 1900, after which her health declined rapidly. In mid-October, she moved back to Phoenix, where she expired on October 26, 1900. Mary A. Lee was buried in Rosedale Cemetery, although the exact location of her grave is no longer known. Although Mary’s probate record states that she had a balance of $325 in an account at the National Bank of Arizona in Tucson, as well as a trunk of personal effects in Phoenix, her executor later stated that these items could not be found. © 2020 by Patricia Gault. Last revised 24 January 2024. If you would like assistance researching our interred, you can find more information on our website. You can contact us at [email protected] at any time. Thank you for your interest to preserve the history of Arizona's pioneers!  Pleas Hutchinson 1887-1941 World War I Veteran Buried in Cementerio Lindo, exact location unknown (image - Unnamed African American soldier, World War I, National Archives) Pleas Hutchinson, African American, was born on May 26, 1887, in or near Forrest City, Saint Francis County, Arkansas. Forrest City was named for Nathan Bedford Forrest, Confederate general and founder of the Ku Klux Klan, but historically it has had an African American majority population.

Pleas was the son of Allen Hutchinson and his first wife, Viney Brandon. After Viney died in 1894, Allen remarried a woman named Leanna Snipes. Although Pleas was thirteen years old in 1900, he had had only about two years of schooling. The federal census of 1910 found the Hutchinsons farming near Eufaula, Oklahoma. Living next to the Hutchinson farm was a family named Perkins. Pleas married Mamie Perkins in 1911. By the time he registered for the World War I draft in 1917, Pleas was already the father of three children. Although the shooting was over by the time Pleas joined the U.S. Army in December, 1918, the Treaty of Versailles was not signed until June, 1919, making Pleas a veteran of World War I. During and after the war, racially-segregated African American units unloaded supplies from ships, cleared out trenches, and buried the United States' war dead. By 1920, Pleas was at home again in Oklahoma, farming near his father and brothers. However, in 1923, the family moved west to Phoenix, Arizona. Pleas and Mamie were living at Buckeye Road and South 15th Avenue when they gave permission for their oldest daughter Olive (or Ollie) to marry in December 1927. Just a month later, their two youngest daughters, Mildred and Zenolia, died of meningitis and polio respectively. Both were buried in the nearby Maricopa County Cemetery. Pleas was the owner of a small farm near South 15th Avenue in 1930, when the federal census listed his assets as $1000. The Hutchinsons had three more children during the 1930s, but the Depression may have cost them their farm. By 1940, Pleas was working for WPA, doing highway construction. Late in 1940, Pleas suffered a stroke brought on by chronic hypertension. He died on May 12, 1941, at his home at 1325 West Sinola Street, Phoenix, and was buried in the Maricopa County Cemetery, now known as Cementerio Lindo. Although the exact location of his grave is not known, he has a cenotaph in the cemetery’s memorial garden. © 2023 by Donna L. Carr. Last revised 8 September 2023. If you would like assistance researching our interred, you can find more information on our website. You can contact us at [email protected] at any time. Thank you for your interest to preserve the history of Arizona's pioneers!  Georgia A. DeLoach Lewis 1872-1909 Wife of John E. Lewis, Barber Buried in Rosedale Cemetery, exact location unknown (image created using Bing AI) Georgia was born on March 10, 1872, in Lancaster, Fairfield County, Ohio. She was one of at least nine children of George W. DeLoach and Mary Stewart, African Americans.

She married Frank M. Hailstock on December 24, 1898, but he died only eight weeks later. On the 1900 federal census of Ohio, Georgia was listed as a young widow, living in her parents' household. Georgia married John Edward Lewis shortly thereafter. John had been a Buffalo Soldier with the 10th Cavalry. Their firstborn son was Frank Hailstock Lewis. Both John and Georgia must have thought highly of Georgia’s deceased first husband to have named their son after him. While in Ohio, Georgia and John also had a daughter Ruth, born in 1905. The Lewis family moved to Phoenix because of Georgia’s health. Her husband John became a well-known barber; he also ran a boxing gym. Unfortunately, Georgia died on August 26, 1909, at the age of 37. She was buried in Rosedale Cemetery, although her grave does not have a marker and its exact location is no longer known. In 1912, John Edward Lewis married Mattie Drake in Norton, Yuma County, Arizona, and he and Mattie had several children together. One was boxer Nathaniel Christy Lewis, biological grandfather of rap artist LL Cool J, as revealed in season 3, episode 7 of the popular TV series, “Finding Your Roots”. John Edward Lewis died on July 17, 1947, and was buried in Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno, California. © 2024 by Donna L. Carr. Last revised 7 January 2024. If you would like assistance researching our interred, you can find more information on our website. You can contact us at [email protected] at any time. Thank you for your interest to preserve the history of Arizona's pioneers!  Granddaughter of Mary Green Buried in Rosedale North, Block 130 Little Daisy Ray, daughter of Moses George Green and his wife Callie Williams, was born in Phoenix on February 11, 1894. Her parents were no longer living together by 1900, when Daisy Ray was recorded on the federal census as living with her mother and a maternal uncle. She died at the age of eight on June 25, 1902, of acute nephritis, and was buried in Rosedale Cemetery, where her grave marker can still be seen.

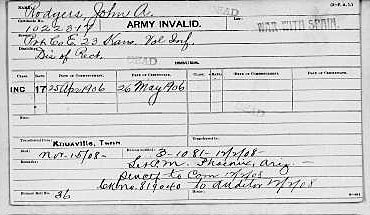

According to her obituary in the Arizona Republican newspaper, “She was a bright little child and was one of the first colored children born in Phoenix. She was quite popular in school and had many friends, to whom her death is a sore bereavement. The funeral will be held this afternoon at 5:30 o’clock in the A.M.E. Church.” In spite of the newspaper’s supposition, Daisy Ray was not one of the first African American children born in Phoenix; that would have been her father Moses and his four younger siblings. Moses George Green was born in 1870 to Mary Green, the very first African American to become a permanent resident of the new little town of Phoenix. Mary is believed to have been born into slavery between 1845 and 1849 in Louisiana; she may have belonged to a Woodhull family. Immediately after the Civil War, however, she was in Arkansas, working as a domestic in the household of Columbus Harrison Gray and his wife, Mary Adeline Norris. Mary Green and her little daughter Fannie came with them by covered wagon from Arkansas to Arizona in August 1868. Mary continued to serve as the Grays’ cook and housekeeper for another twenty years, during which time she gave birth to four more children. In 1887, she left the Greys’ employ to take up a homestead near Tempe with her adult children. Although Mary herself seems to have been illiterate—she signed her 1892 homestead patent with an X--it appears that her children received at least six years of schooling. When Mary died in 1912, she was buried in Greenwood Cemetery’s Section 10, which was reserved for what might have been considered Phoenix’s ‘black bourgeoisie’. Among her descendants was great-granddaughter Helen K. Oby Mason (1912-2003), who launched Phoenix’s Black Theater Troupe in 1970. © 2021 by Donna L. Carr. Last revised 4 February 2021. To obtain a copy of the sources used for this article, please contact the PCA to make a suggested donation. Grave marker photo courtesy of the Pioneers’ Cemetery Association, Inc.  Spanish-American War Veteran Buried in Rosedale Cemetery, exact location unknown John A. Rodgers, African American, was born around 1873 in Senatopia, Mississippi. On July 12, 1898, he enlisted in Company E, 23rd Kansas Volunteer Infantry. It was a segregated unit drawn from several Kansas communities founded by freedmen in the post-Civil War era. Black units were being sent to Cuba on the theory that African Americans would have some immunity to tropical diseases. Unfortunately, this proved not to be the case.

By the time the regiment reached Santiago, Cuba, in August 1898, the shooting war was already over. The 23rd Kansas was tasked with guarding 5000 defeated Spanish soldiers awaiting transport back to Spain. During much of his tour of duty in Cuba, Rodgers was laid up with dysentery and then malaria. On March 1, 1899, the 23rd Kansas boarded a transport ship for New York City. Rodgers was discharged on April 10 at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. He moved to Hot Springs, Arkansas, where he married a woman named Annie Pickett on October 3, 1900. Rodgers’s military service had left him debilitated and unfit for heavy physical labor. Pension records show that he was 6 feet 4 inches , unusually tall for that era. He became a tailor, possibly because readymade clothing did not fit him and he had to sew his own anyway. On May 26, 1906, Rodgers applied for and received a disability pension (Invalid Certificate #1022317). Owing to his bout with dysentery in Cuba, he was afflicted with large, protruding piles (hemorrhoids). Initially, he received $10 a month. Over the years, payment was increased to $17 a month. In mid 1908, John Rodgers was experiencing heart problems, although he was only 35 years old. He left his wife in Hot Springs and went to Los Angeles, possibly to the Old Soldiers Home in Sawtelle. Thereafter, he moved to Phoenix, Arizona, where he rented a room at 30 North 2nd Avenue. To support himself, he placed ads in the local newspaper, asking for work repairing old carpets and refurbishing used clothing. John A. Rodgers died on November 14, 1908, of aortic insufficiency, mitral regurgitation, and hypertrophy of the left ventricle. He was buried in Rosedale Cemetery. Several days after Rodgers’ death, Marshal Moore of Phoenix received an urgent letter from a Mrs. Jennie Reeves, asking the marshal to take charge of Rodgers’ body and effects. She also said that the deceased was a military veteran and asked that Rodgers’ body be returned to Arkansas for burial or sent to the National Cemetery. Her request could not be accommodated, however, because Rodgers was already buried and no one could attest to Mrs. Reeves’ legal rights to Rodgers’ property. © 2022 by Donna Carr. Last revised 1 November 2022. To obtain a copy of the sources used for this article, please contact the PCA to make a suggested donation. Image: Army Invalid card for John A. Rodgers, 1908, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)  African American Barbers and Porters Five family members, buried in Rosedale and City Loosley (no markers) The Belt Cook family were African Americans who lived in Phoenix from 1887 on.

Belt Cook was a light-skinned mulatto, born between 1845 and December 1846 in Maryland. Around 1866, he married Rebecca Hall, who had been born in Pennsylvania. He and Rebecca had fifteen children, nine of whom lived to adulthood. The birthplaces of the Cook children show that the family moved back and forth across the country between 1869 and 1887, living in Nevada and California before finally coming to Arizona. Since Belt and his son Charles were barbers and one of Belt’s sons-in-law was a porter, they may have been employed by the railroads or simply followed the railroads west. Belt Cook’s skill as a barber made it possible for him to find employment readily. In 1869, the family was living in Austin, Nevada, in a mixed race community with other porters, skilled craftsmen and even lawyers as neighbors. By 1873, the family was in Los Angeles, California. 1881 saw the Cook family residing in the boom town of Globe, Arizona. However, as placer mining gave way to large-scale operations like the Old Dominion mine, Globe reverted to the status of a small frontier town, and the Cooks moved on to Phoenix in 1887. The Cook children seem to have received a good education for the times. In 1900, son Elias Belt Cook was a member of the McKinley Club, a political organization of prominent colored men. No matter their position in the community, though, the Cooks were still subject to the illnesses of the day. Daughter Eva died in 1894 of what was probably meningitis. Charles’s wife Lola succumbed to tuberculosis in 1897. Daughter Lillie passed away in 1902, and son William Thomas died of tuberculosis in 1909. All are buried in the Pioneer & Military Memorial Cemetery, as is Belt Cook’s older brother Elias. Entries in a 1912 city directory show Belt Cook as a barber at 20 North 2nd Street. Charles was a barber just a few blocks away at 3 East Jefferson. By 1920, Belt and Rebecca were retired and living with their eldest son John. Belt Cook died February 28, 1929, and Rebecca died in 1933. They, as well as their son Elias, are buried in Greenwood Cemetery. At least one of their surviving daughters, Mary Elizabeth Cook Roberts, was still living in Phoenix when she passed away in 1953. © 2021 by Donna L. Carr. Last revised 24 February 2021. To obtain a copy of the sources used for this article, please contact the PCA to make a suggested donation. Free graphic courtesy of ClipArt Library  Barber and Letter Carrier Buried in Rosedale Cemetery, North Section John Bolton arrived in Phoenix about 1890. During his short life of 36 years, he journeyed from Kansas to San Diego, California, before relocating to Phoenix for his health.

Bolton had been born in Tennessee. African-American and a barber by trade, Bolton began his career in Phoenix by working in Frank Shirley’s barber shop, The Fashion. Bolton’s wife Hattie worked at the Alhambra on Papago. Bolton was not a man to be easily intimidated. While walking home from work late in December, 1892, he was accosted by a thief. Seizing a brick, Bolton hit the footpad in the face and made his escape unscathed. Soon after his arrival in Phoenix, Bolton became active in local politics. He was elected as an alternate delegate to the Republican National Convention from Maricopa County in April, 1896, the year in which William McKinley won his first term as president. In June 1897, Bolton contracted to have a one-story brick residence built at Fillmore and North 2nd Street. A well-read man, Bolton was elected president of the Colored Literary Society in December, 1897. As Bolton prospered in his profession, he opened a barber shop in a more prestigious location, the new Adams Hotel in downtown Phoenix. In September 1898, he also took a civil service exam and became one of the first black letter carriers in the city. Bolton seems to have been a bit of a practical jokester. When he made the acquaintance of African American men recently arrived in Phoenix, he was not above engaging in a little hazing. First, Bolton would suggest that his new companion accompany him to a local park to meet some of the town’s young ladies. Once there, a confederate would jump out of the bushes and fire a couple of gunshots, causing the poor chap to take to his heels with Bolton close behind. Not until the newcomer stopped to draw breath would Bolton innocently remark that the shooter must have been the overprotective father of one of the young ladies. Unfortunately, the desert air was not restorative for John Bolton and he died at his home on North Second Street of a lung hemorrhage on December 26, 1902, leaving behind his wife and son. The funeral was attended by his many friends and customers. His grave in Rosedale Cemetery North is marked with a simple headstone. © 2020 by Derek Horn and Donna Carr. Last revised 18 December 2020. To obtain a copy of the sources used for this article, please contact the PCA to make a suggested donation. Photo Courtesy of the Pioneers’ Cemetery Association |